SEOUL—Wendy Arbeit had an unusual vacation announcement during a recent talk with her boss at the University of California school system. “I’m going to North Korea! ” the 47-year-old said.

Weeks later, Arbeit found herself in a restaurant at the “Namsan Hotel,” where a Budweiser refrigerator case sat in the corner. She hoisted a North Korean flag in each hand and posed in front of a celebratory cake. “Congratulations,” it read in Korean. “195 Countries.”

She had visited every nation on Earth—except one. In recent days, Arbeit, a dual U.S.-German national, notched her final destination after North Korea dropped Covid-era restrictions that had blocked Western tourism since January 2020.

“I’ve been waiting for North Korea for five years,” Arbeit says. “The experience was good enough that I would go back.”

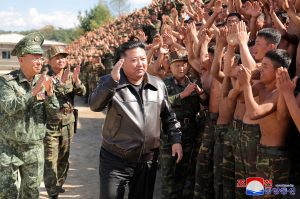

The first Western tourists are trickling back into the totalitarian Kim Jong Un regime. They’re goal-oriented globetrotters, North Korea nerds and YouTubers willing to drop everything to visit one of the world’s most recalcitrant—and potentially dangerous—places.

The vacationers saw North Korean singing schoolchildren tout Kim as the “very best in the world” as a large screen showed animated missiles rain from the skies. Itineraries included demonstrations of traditional bean cake making, visits to a beer brewery and dining on cold buckwheat noodles, kimchi and even flaming snails.

Some Korean-speaking visitors belted out Kim regime propaganda tunes at a local karaoke bar, where the top shelf had bottles of Chivas Regal and Ballantine’s. Smartphones were everywhere.

With just days of advance notice, a pair of tour groups brought roughly two dozen Western visitors to North Korea’s Rason special economic zone, near the Chinese and Russian borders. Their five-day trip ended Feb. 24. Nearly all flew into Beijing, before making their way to another Chinese city and entering North Korea.

Mike O’Kennedy, a 28-year-old YouTuber with a British passport, says he felt a mixture of excitement and nervousness throughout the trip. His unease peaked at the “Friendship House,” which celebrates relations between North Korea and Russia. Local tour guides asked if he would sign the visitors’ guest book.

Pen in hand, O’Kennedy recalled his mind going blank, so he wrote something he thought a child might scribble on a holiday card: “I wish peace to the world.”

The inscription caused the North Koreans to freeze. “Do you think this is an appropriate thing to write?” one asked.

O’Kennedy offered an apology. A few silent seconds passed. Eventually, O’Kennedy shuffled out of the Friendship House and reached for cigarettes. He received no reprimand.

“Looking back,” O’Kennedy says, “it probably was a stupid thing to write.”

Before the pandemic, North Korea welcomed around 350,000 foreign travelers in 2019—some 90% of them Chinese, according to some independent estimates. A year ago, North Korea began accepting Russian tourist groups. But access didn’t widen until February.

The State Department since 2017 has banned U.S. citizens from entering North Korea. But dual-passport holders aren’t blocked from traveling there.

Nicolas Pasquali, a 32-year-old with Italian and Argentinian passports, also needed North Korea to finish his quest to visit all countries. Pasquali said he had visited at least 20 nations engaged in war, been kidnapped by a terrorist group in Mauritania and stood accused of espionage in Iraq.

By those comparisons, Pasquali says, North Korea felt comfortable. “I felt very safe, very good.”

North Korea, for now, has only opened Rason to non-Russian travelers. That excludes Pyongyang, the capital city and the country’s most-popular tourist destination.

The tour operators that recently brought in the Westerners—Koryo Tours and Young Pioneer Tours—say demand remains robust. “We don’t cold call anyone. People reach out to us,” says Rowan Beard, a co-founder of Young Pioneer Tours.

The Western travelers paid around $725 for the tour, which covered lodging and meals though not initial travel into China. North Korean guides followed them wherever they went. Visitors were told to use Chinese yuan. They splurged on propaganda art and “7.27” cigarettes—allegedly Kim Jong Un’s favorite brand and named after the date when the Korean War armistice was signed, July 27, 1953.

At his hotel, Pierre Biot, 30, spotted for purchase rare English and French translations of Kim Jong Un’s “Aphorisms,” a collection of his public statements, and a red book titled “Great Man” about Kim Il Sung , the current leader’s grandfather and country founder. “I bought a ton,” says Biot, who is French.

Luca Pferdmenges, a German national, has three million followers on TikTok as a travel blogger. A former circus performer, he records himself juggling in every country he visits—though this proved to be a challenge in North Korea. The 23-year-old says throughout the trip, he had to earn the trust of his North Korean tour guide, who didn’t let him film the juggling video in Rason’s city center at first. On the trip’s final day, the guide relented.

“I didn’t do any bulls— during the tour,” he says. “You don’t want to fight with your guides.”

Grabbing a karaoke-machine mic at a North Korean bar, Benjamin Weston, who led the Koryo Tours group in Rason, couldn’t choose any Western songs. They weren’t available. So, Weston, a dual U.K.-New Zealand citizen who speaks Korean, opted for “Don’t Advance, Night of Pyongyang,” a soulful ballad.

Mid-song, Weston noticed North Korean locals had begun recording him with their smartphones. “At which point it was a bit nerve-racking,” he says.

Kayl Grau, 21, a college student studying computer science, says one of the North Korean tour guides demonstrated how she honed her English. She pulled up clips from Disney films on her smartphone , singing lines of “Let It Go” from the film “Frozen.”

Grau and other travelers visited a middle school, where they spoke English with some North Korean students. One asked Grau where he is from, and he said Australia.

“I would really like to visit Australia,” the girl responded, “but I’m really sad because I won’t be able to.”

Write to Timothy W. Martin at Timothy.Martin@wsj.com